The following article was originally published by the Sun Sentinel on August 19, 2015.

Next month, when Pope Francis visits the United States, one stop on his itinerary will be a prison outside of Philadelphia. He has visited prisons in Italy and other countries to remind us of the dignity of even those convicted of crime. Pope Francis has said, “God is in everyone’s life. Even if the life of a person has been a disaster, even if it is destroyed by vices, drugs or anything else — God is in this person’s life.”

to remind us of the dignity of even those convicted of crime. Pope Francis has said, “God is in everyone’s life. Even if the life of a person has been a disaster, even if it is destroyed by vices, drugs or anything else — God is in this person’s life.”

While conditions in U.S. prisons might be a bit more humane than those in the notorious Palmasola prison he visited in Bolivia last month, our criminal justice system is nevertheless broken, and it needlessly continues to break up families and communities throughout our nation.

As a nation we incarcerate more of our population than any other Western country, more than even the Soviet Union did. Today, the United States has more than 2.2 million people in prison on any given day — and in the course of a year some 13.5 million passed through our correctional institutions.

In Florida, our state prisons, which house some 100,000 people, have been tainted by scandals in recent years — with various allegations of prisoner abuse and even murder by guards still being investigated.

How did this come about? There are lots of reasons, of course. The crisis in our families — the breakup and dissolution of American families, especially among the poor — certainly left many young people rudderless. Many did not only lose their way; they never learned the way.

Access to better legal counsel and resources often allow the rich and better-educated offenders to defer or avoid prison. The incarcerated tend to be those less educated, the mentally ill, drug addicts or the poor. And because of ill-considered tougher sentencing laws and tougher parole laws that seek more to punish than to rehabilitate, our prison populations continue to grow. “Three strikes” laws often end up sentencing minor criminals to a lifetime of jail for what are relatively petty third offenses.

Justice is supposedly blind — but given the inequities of the criminal justice system today, one could rightly say that justice is crippled.

Our Judeo-Christian tradition has always called for the humane treatment of prisoners and has emphasized that imprisonment should lead to the rehabilitation of the prisoner so that he can return to society and resume his place as a productive citizen. The reality of prisons today is far from this ideal.

While society needs to be protected from the worst among us, there is little effort to rehabilitate the nonviolent and the misguided. And while our Constitution prohibits cruel and unusual punishment, what we see happening in our prisons is cruel and inhuman. The spread of infectious diseases in prisons, including AIDS, and the sexual violence that occurs within prison walls point out just how inhuman conditions are in our nation’s prison system today.

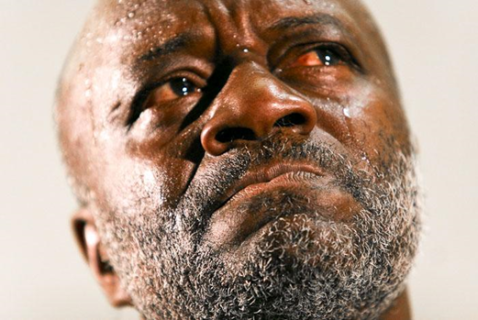

All this reflects the sad reality of the incarcerated today, whether they are in a small county jail or a large federal prison. Their world is one of pain and despair. Because nobody wants to live next door to a correctional institution, they are usually built in isolated rural areas — and so prisoners end up “warehoused” far from their families — and so, “out of sight, out of mind,” the rest of society allows itself to simply ignore them.

Violence begets violence: Man’s inhumanity to man consists not only of crime itself but also how we as a society treat the wrongdoer. The inmate is our brother or sister in Christ, a child of God who, in spite of whatever crime he or she might have committed, does not forfeit his or her dignity as a child of God.

As a church we must proclaim and promote the respect of each person’s dignity — this must include the unborn, the handicapped, the migrant, the elderly … and it cannot fail to include the prisoner as well.

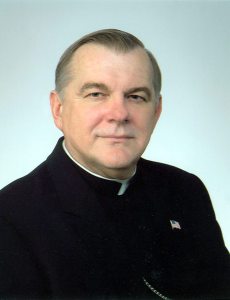

Here in the Archdiocese of Miami, many of our priests, deacons and faithful minister to the incarcerated. Their ministry is truly a work of mercy. They take to heart Jesus’ words in his parable of the Last Judgment (Matthew 25): “I was in prison and you visited me.”

After all, Jesus himself was imprisoned and suffered crucifixion, the means of capital punishment of his time. And from the cross, he beatified a common criminal whom history now knows as the “Good Thief” because he “stole” heaven — getting there even before the sinless Virgin Mary.

Pope Francis will remind us in his visit to a U.S. prison this September, “God is in everyone’s life.”

Most Reverend Thomas G. Wenski is Archbishop of Miami and is chairman of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ (USCCB) Committee on Domestic Justice and Human Development.